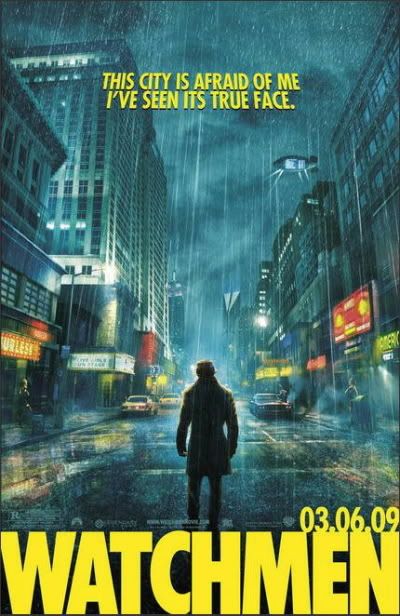

2009/USA/Directed by Zach Snyder

While it’s not the first film based on a comic book to be aimed squarely at an adult audience (think Sin City), Watchmen may be the first Hollywood film featuring what appear to be ‘classic’ superheroes that explicitly excludes kids from its potential audience demographic (and sacrificing quite a bit of box-office potential in the process).

While it’s not the first film based on a comic book to be aimed squarely at an adult audience (think Sin City), Watchmen may be the first Hollywood film featuring what appear to be ‘classic’ superheroes that explicitly excludes kids from its potential audience demographic (and sacrificing quite a bit of box-office potential in the process).

Based on the landmark 1986 graphic novel, written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Dave Gibbons (originally published by DC Comics as a 12 issue mini-series), Watchmen casts itself in the reality based world on mid-1980s America. However, unlike Batman Begins and The Dark Knight (which cast Batman in a recognisable real world), the 1980s depicted in Watchmen is that of an alternative reality. A wonderful opening title sequence, accompanied by the laconic strains of Bob Dylan’s The Times They Are-A-Changing, takes us on a journey through the past decades as they happened within the film’s world: America has won the Vietnam War, Nixon is still the President of the USA, and a group of self-styled costumed superheros calling themselves ‘The Watchmen’ have virtually taken over the role of the uniformed police.

By the 1980s, however, things have changed. Superheroes have been outlawed, and America and the USSR tetter on the brink of annihilating each other through nuclear assault. When one of the original Watchmen, the cigar chomping Comedian, is thrown to his death out of a high rise window, the remaining members of the group start to debate whether or not the Comedian’s murder was an isolated incident, or if they are caught up in a plot to rid the world of all its former masked heroes. Around this simplistic but effective noirish set-up, the story piles on layers of exposition and character development and interaction, as the Watchmen slowly find themselves drawn back to each other to confront a plot to assure world peace by the most insidious of methods.

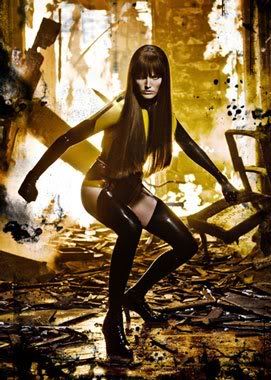

The characters in Watchmen were inspired mostly from obscure comic book characters of the 1940s, something which is clearly evident in the style of their outfits and mannerisms. Nite Owl features owl themed gadgets, while the original Silk Spectre (her daughter goes on to take up the mantle) looks like she stepped straight out of the nose art of an American World War II bomber. Dr Manhattan, formerly the scientist Jonathan Osterman who was transformed into a quantum being that can command particles after he was trapped in a ‘Intrinsic Field Subtractor’ in 1959, is the only Watchman with any real super powers, and recalls the great science-fiction characters often found in Marvel Comics in the early 1960s.

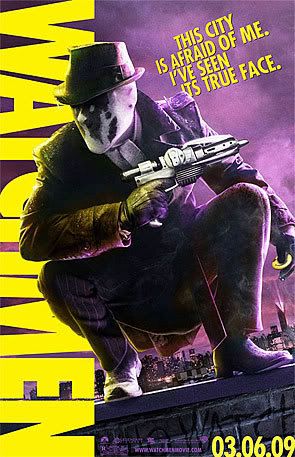

Certainly, these aren’t your ordinary superheroes, and while they may break the clichés usually found in this genre, they do often conform to other well-established character stereotypes (the Comedian, for example, is a misogynistic rapist and woman killer with incestuous leanings, the type we have seen many times in other films outside of the superhero genre). By far the most interesting, and strongest, character is Rorschach, a small statured but lithe and volatile character who wears a grey mask that features a constantly changing ink blot pattern on its face. Continuing the fight against crime despite his outlaw status, the scenes where Rorschach is locked up in a brutal prison (where he must confront many of the sociopaths whom he helped put away), as well as a flashback sequence where he tracks down a child killer and makes his transition from crime fighter to vigilante, provide some of the film’s most powerful and memorable moments.

At nearly three hours long, Watchmen demands a lot of attention and concentration from its audience. Let your mind wander for a moment, or duck out for a quick bathroom break, and you may struggle to find your way back into the film’s narrative. Director Zach Snyder (300) deserves credit for treating his source material with respect, as well as for eschewing a big name cast in favour of an ensemble of lesser names who work well together, although Jackie Earl Haley as Rorschach provides the only real stand-out performance.

Technically, the film is a mixed bag. Some moments of stunning visual impact are offset by some rather lacklustre CGI effects, while the soundtrack too often utilizes pop music numbers in an attempt to create an ironic juxtaposition with the violence occurring on screen.As he has done with every filmic adaptation of his works (From Hell, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, V for Vendetta), writer Alan Moore, who hates Hollywood and its ‘blockbuster’ mentality with a passion, has refused to allow his name to be attached to the project, with the film’s credits making no mention of the man whose pen inspired it (Moore also refuses any monetary remuneration for films based on his work, donating all of his fees and royalties to the other artists who were involved in the original comic book project).

Ultimately, Watchmen succeeds as a well-crafted and occasionally intelligent piece of adult filmmaking, but I found it to be a somewhat dispassionate and uninvolving cinema experience – something to be admired rather than enjoyed, which is an admirable accomplishment on its own, but not exactly the first thing I look for in a comic book film.

Review by John Harrison

Copyright 2009