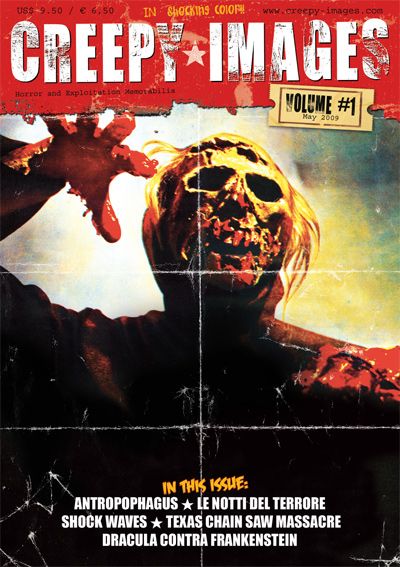

For further details and ordering info visit the Creepy Images website at: www.creepy-images.com

Friday, May 15, 2009

CREEPY IMAGES

For further details and ordering info visit the Creepy Images website at: www.creepy-images.com

Saturday, May 9, 2009

BLIMEY! THE HAMMER STUDIO COMEDIES

By 1970, England’s Hammer Studios, who had established their reputation during the late 1950s and 60s as the undisputed kings of gothic, colour saturated horror cinema, had begun to fall on hard times. Finding it increasingly hard to compete with the emergence of the new wave of independent American horror, which upped the ante with flicks like George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), Hammer tried to stay relevant (and commercially viable) by introducing a stronger mix of violence and sex in their films, particularly their female-led ‘Karnetsin’ vampire trilogy: The Vampire Lovers (1970), Lust for a Vampire (1971) and Twins of Evil (also released in ’71). While these films still managed to find an audience, and today are rightfully regarded as cult classics of a kind, the rich atmosphere and unique class which Hammer had so beautifully generated in films like Horror of Dracula (1958), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) and The Curse of the Werewolf (1960) had all but evaporated, and the writing seemed to be on the wall for the company.

In 1959, Hammer adapted the popular Granada TV series The Army Game into a feature film, retitling it I Only Arsked, and featuring future Carry On movie regulars Bernard Bresslaw and Charles Hawtry amongst its cast. The success of I Only Arsked (which took its title from a phrase which Bresslaw often used on the series) may have been a deciding factor in prompting Hammer to try and boost their coffers by adapting another popular television comedy into a feature.

When On the Buses debuted on TV in 1969, it was an instant success, both in England and in a number of countries abroad, especially Australia. Set in the disorganized Luxton & District bus terminal, the show starred Reg Varney as bus driver Stan Butler, who together with his leering conductor Jack Harper (Bob Grant) spent as much time chasing the ‘clippies’ (female bus conductors) as they did on their bus route. Constantly trying to keep them in line was their ever frustrated, Gestapo-like Inspector ‘Blakey’ (Stephen Lewis), whose catchcry of “I’ll get you, Butler” became one of British television’s most enduring phrases. Subplots in the series were usually provided by Stan’s dysfunctional, constantly bickering family – mum (Doris Hare in most episodes), sister Olive (Anna Karen) and his brother-in-law Arthur (Michael Robbins).

Hammer’s 1971 film version of On the Buses was directed by Harry Booth, from a screenplay by Ronald Wolfe and Ronald Chesney. The plot has the bus company branching out to employ women drivers, something which doesn’t make Stan and union boss Jack very happy, as it threatens to reduce their overtime. One of the subplots has the bumbling Olive taking a job at the bus terminal canteen, then losing it when she falls pregnant to Arthur. There’s also time for plenty of girl chasing, and fans of cult horror director Pete Walker will get a kick out of seeing Ivor Salter (the lorry driver in House of Whipcord) bob up as a policeman. The inclusion of a cheesy but snappy theme song ("Oh, it’s a great life on the buses” ), performed by one Quince Harmon, helps make On the Buses an enjoyable slice of grimy UK working class comedy.

Shot at the EMI-MGM Studios, as well as in the surrounding streets of Borehamwood, On the Buses proved to be a huge hit for Hammer, with the UK gross even surpassing that of the then-current James Bond film, Diamonds Are Forever. An inevitable sequel was soon put into motion, and Hammer set up a competition for the readers of the The Sun newspaper to come up with an appropriate title. The aptly-named Bob Butler (a real life bus driver) won the thousand pound first prize with his title Mutiny on the Buses, which was released in 1972 and once again directed by Harry Booth from a Ronald Wolf and Ronald Chesney screenplay (Wolfe and Chesney had also created the television series). Mutiny saw the Luxton bus company expanding their services to include a tour of the Windsor Safari Park (an idea that quickly ends in disaster after Butler and Blakey conduct a test run of the tour), while Arthur becomes a bus driver after getting retrenched from his job with British Rail.

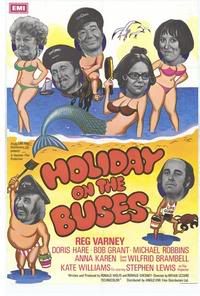

The third and final entry in Hammer’s Buses films, Holiday on the Buses, appeared in 1973, and was something of a step-up from the rather bland Mutiny. While Wolfe and Chesney once again scripted, director Bryan Izzard (a veteran of 17 episodes of the television series) was brought in to give the story and characters a more familiar feel, along with a boost of energy. Holiday sees Butler, Jack and Blakey all getting the chop from the bus company, only to resurface at a tacky Pontin’s holiday resort, where Blakey has taken a job as head of security, while Stan and Jack conducts bus tours of the area for the holidayers. As in the first two films, Stan seems to do all the work chatting up one of the lovely young birds, only to have his good mate Jack pounce on her behind his back. What a friend! (As Jack himself explains it to Stan: “I don’t know what you’re so worked up about, mate. It’s only a bit of crumpet…There’s plenty more of that about” ). Bob Grant’s hair has turned almost silver in this movie, and Stan’s family, more white trash than ever, turn up looking for a cheap vacation (which gets off to a not so wonderful start when most of their clothes end up in a dirty river before they’ve even reached their destination). Guest stars included Wifred Branbell (Steptoe & Son) as an old lech who hits on Stan’s mum, and Kate Williams (Eddie Booth’s wife in Love thy Neighbour) plays a nurse at the holiday resort who, for some strange reason is attracted to Blakey (but also can’t resist the charms of Jack).

Shortly after the release of Holiday, Reg Varney left the television series. Although the show struggled on briefly without him, Hammer wisely decided against making any further On the Buses films.

But the studio was far from done with their television adaptations. Apart from Holiday on the Buses, 1973 also saw the release of a Love Thy Neighbour feature, which brought together all the regulars from the series (which had debuted in 1972). Produced by Hammer vet Roy Skeggs and scripted by the show’s creators, Vince Powell and Harry Driver, the film was directed in a rather flat and lacklustre fashion by John Robins. Cantering around a local ‘Love Thy Neighbour’ competition, the Love Thy Neighbour film recycled many of the same racial jokes and gags from the series, with the only real new angle being the introduction of Eddie Booth’s mother, who comes to visit and ends up going out with Bill’s father.

In the following twelve months, four more Hammer TV adaptations were released: That’s Your Funeral, Man at the Top and Nearest & Dearest all appeared in 1973, while their version of Man About the House followed in 1974. I don’t recall ever seeing any of these films at any point, so I’m not entirely sure about the quality of them, although I imagine for the most part they would be pretty dire and dated, but as a sucker for almost any early seventies UK working class comedies, I'd certainly be keen to pick them up should they ever surface on disc locally.

Above: CD compilation of music from Hammer's comedy films, released in the late 1990s.

Oh! It's a great life on the buses,

Oh! It's a great life on the buses,

Oh! It's agreat life on the buses,

There's so much feeling on the buses,

It's so exciting on the buses,

There's always gay life on the buses,

It's so romantic on the buses,

Oh! It's a great life on the buses,

Music by Geoff Unwin.

Friday, May 1, 2009

THE GOLDEN AGE OF BURLESQUE CINEMA

Some people might be surprised to discover that during the height of its 1950s popularity, the art of burlesque thrived not only on the stage but on the screen as well.

Of course, even those with just a passing interest in burlesque are aware of such films as Striporama (1953), Varietease (1954) and Teaserama (1955), all of which attained a new level of notoriety in the early-1990s, thanks to the appearances in them by Bettie Page, whom at that stage had been rediscovered and established as the defining cheesecake pin-up of her generation. Some people may even be aware of mainstream films which flirted with the art, such as the 1943 Barbara Stanwyck B-picture Lady of Burlesque. However, the burlesque film genre runs surprisingly much deeper than these few titles.

While traditional burlesque as a live performance art has been around for over one hundred years, its cinematic popularity peaked in the in the first half of the fifties. Spurred on by a slight relaxing in film censorship laws, as well as the huge influx of young GIs who had returned from combat in Europe and the Pacific – where they had no doubt been exposed to forms of entertainment more risqué than what they had been used to seeing at home – the burlesque film genre began to appear more and more often, usually screening in small, low-rent cinemas that catered to exploitation films, as well as in men’s clubs and even as warm-up entertainment for live girlie shows themselves.

Extremely simplistic in their production, most burlesque films from this period were little more than live shows captured on celluloid, an economic move on behalf of the filmmakers which fifty years later makes them authentic (and important) time capsules of their era, as they often included not only the dancing and stripteaser girls, but the ‘comedy’ and variety acts that were used to pad out the shows and keep the audience entertained while the gals backstage changed costumes and got ready to take the stage once again. Apart from the aforementioned Bettie Page, other notable performers who appeared in vintage burlesque films include Lili St. Cyr, Tempest Storm and Blaze Starr.

One of the most popular types of burlesque film were those which focused on the naughty nightlife of a particular (and usually exotic) city. The notorious George Weiss (Glen or Glenda) was one exploitation producer who favoured this style of film, putting together a string of ‘After Midnight’ titles in the early-fifties, including Paris After Midnight (1951), Bagdad After Midnight (1954) and Tijuana After Midnight (also 1954). Other similar titles in this genre include Burlesque in Harlem (1950), Burlesque in Hawaii (1953), Naughty New York (1959) and 1964’s Naughty Dallas (directed by schlockmeister Larry Buchanan of Mars Needs Women fame and filmed inside Jack Ruby’s nightclub).

Occasionally, some burlesque films would try to incorporate some semblance of a plot into them. In Joseph P. Mawra’s The Peek Snatchers (1965), a small TV-like device discovered by two perverts allows them to tune in and watch dancing girls perform on stages all over the world, while Striptease Murder Case (1950) injects some cheesy whodunit elements into its proceedings (with predictably ludicrous results).

Apart from features, burlesque shorts were also a popular form of entertainment amongst hot blooded men during the 1950s. These were usually shot on 8mm and presented as ‘loops’ in peep machines, or sold through the pages of men’s magazines for home viewing (they would become particularly popular at stag parties).

As nudie-cutie and sexploitation films became more popular – and risqué - in the early 1960s (thanks to filmmakers such as Russ Meyer, Doris Wishman and Herschell Gordon Lewis), the burlesque genre eventually withered and died, only to live again decades later, thanks to the home video and DVD revolutions.

Sources:

Many of the films mentioned in this article – as well as many others – are available on VHS and DVD from Something Weird Video (

John Harrison 2009